The Bath Riots of 1917 and the Enduring Legacy of Carmelita Torres

To speak of Latina’s struggle for human rights is to speak of Carmelita Torres.

Like many other Mexican women of the 1910s, Carmelita Torres crossed the border at El Paso every day at 7:30 a.m. to clean American homes.

Border agents lined up each and every worker, stripped them naked, and searched in a demeaning move to control an outbreak of typhus. However, the humiliation did not end there. Many of the Mexicans crossing the border were forced to take baths of gasoline, kerosene, and vinegar to “delouse” the workers.

Until Carmelita Torres said, “Enough.”

Another chapter in the endless story of immigrant mistreatment in the United States

In 1917, El Paso Mayor Thomas Calloway Lea Jr. requested a quarantine to prevent the spread of typhus supposedly by “dirty, lousy, destitute Mexicans” arriving in El Paso from Ciudad Juarez, Mexico.

This demographic movement was a consequence of the violence of the Mexican Revolution but also because of a labor demand on the other side of the border.

Under the argument of disease control, U.S. authorities established the so-called “disinfection station” under the old Santa Fe International Bridge.

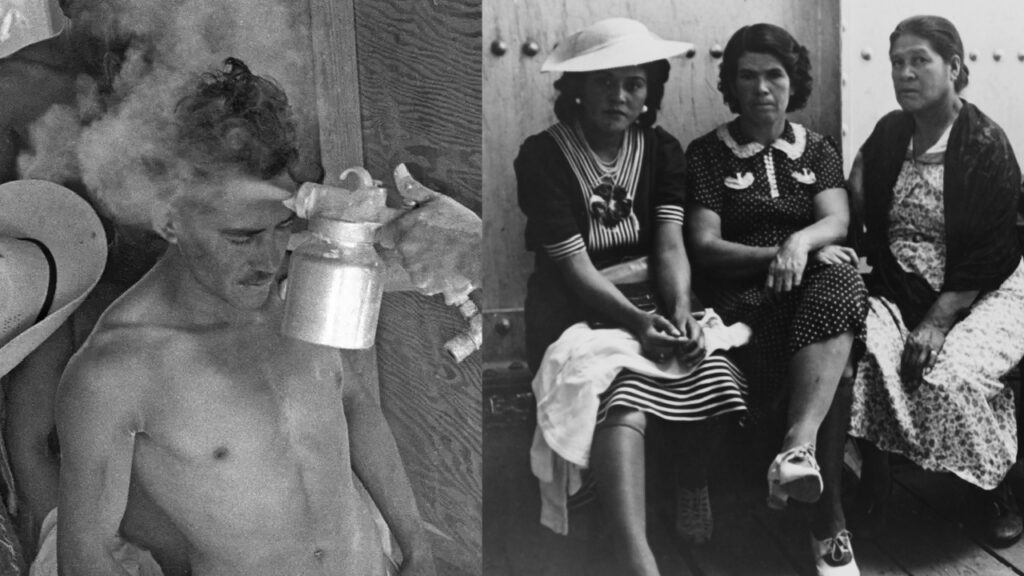

According to reports at the time, men and women were placed in separate disinfection facilities. They were stripped of all clothing and valuables. Their belongings were then vaporized and treated with toxic cyanogen gas while the individuals themselves were examined for lice.

If a man was found to have lice, his hair was shaved close to the scalp. Women’s hair was dipped in a highly flammable vinegar and kerosene mixture, covered with a towel, and allowed to stand for at least 30 minutes.

After inspection for lice, people were gathered in a shower area. They were sprayed with a liquid made of soap shavings and kerosene oil. After collecting their disinfected garments, they received a vaccination and were given a certificate stating they had completed the process.

And then Carmelita Torres stood up

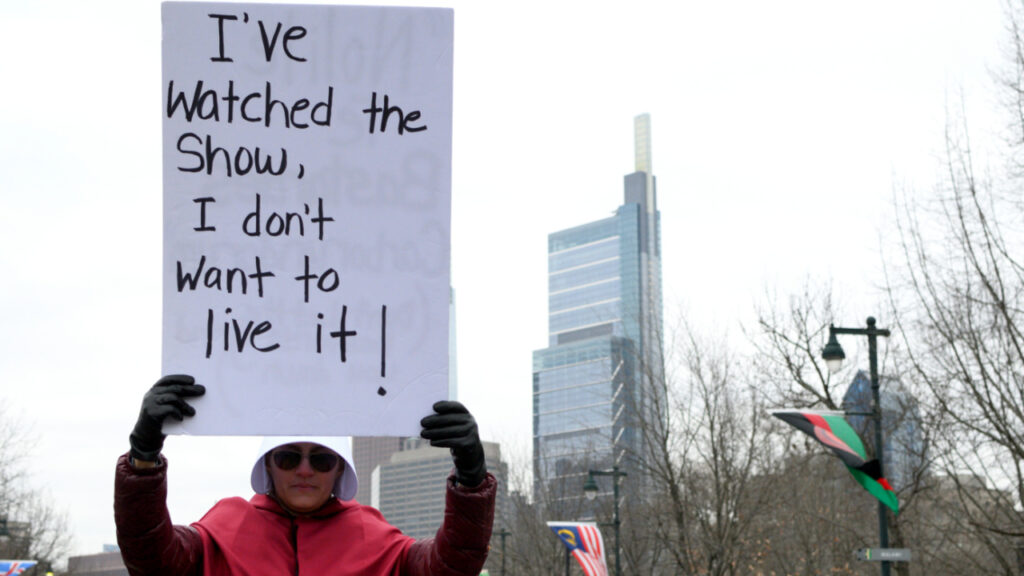

It was 7:30 in the morning on January 28, 1917, when Carmelita Torres was crossing the border to work. A U.S. customs agent detained Carmelita and demanded that she submit to inspection and the consequent toxic bath. But the young woman refused.

According to David Dorado Romo in his book “Ringside Seat to a Revolution,” Carmelita convinced the other 30 women traveling with her to get off the electric trolley. Seeing what was happening, other workers joined the protest that today is known as the “bath riots.”

More than 200 women proceeded to block the entrance to El Paso, throwing rocks at the agents.

Headlines the next day described Carmelita as an “Auburn-haired amazon” who led a “feminine outbreak” at the Santa Fe Street bridge. Other media described “women ringleaders of the mob” who “hurled stones at American civilians.”

And while the riots lasted three days, the border baths lasted decades.

Carmelita Torres’ reasons went beyond the humiliating inspections

The Mexican workers who crossed the border every day didn’t just suffer the consequences of the toxic buildup in their bodies. Carmelita Torres and the other women also learned that Border Patrol agents supervising the searches were taking pictures of the naked women and sharing them at local bars.

Although the women’s anger was enough to get the attention of the media and the government, little changed. Carmelita Torres, who some call “the Latina Rosa Parks,” was arrested and was never heard from again.

The baths continued, and, Dorado Romo recounts, fumigations got worse. By 1917, 127,000 Mexicans were “deloused” and fumigated at the border, and the practice lasted for decades.

However, this did not happen at any other port of entry in the country, where millions of European immigrants arrived fleeing conflicts in their home countries.

This only happened on the Mexican border, and it only affected hundreds of thousands of Mexicans. Until, like many other times, one woman stood up and fought against oppression.