The First Feminist Congress Was a Blueprint for Latina Political Power. Here’s What We Can Learn (and What to Leave Behind)

In 1916, the First Feminist Congress sparked big debates on education, divorce, work, and voting, plus who got left out.

If you picture feminism in Latin America as something that “arrived” decades later, in capital cities, through academic debate, the story of the First Feminist Congress makes that story fall apart fast.

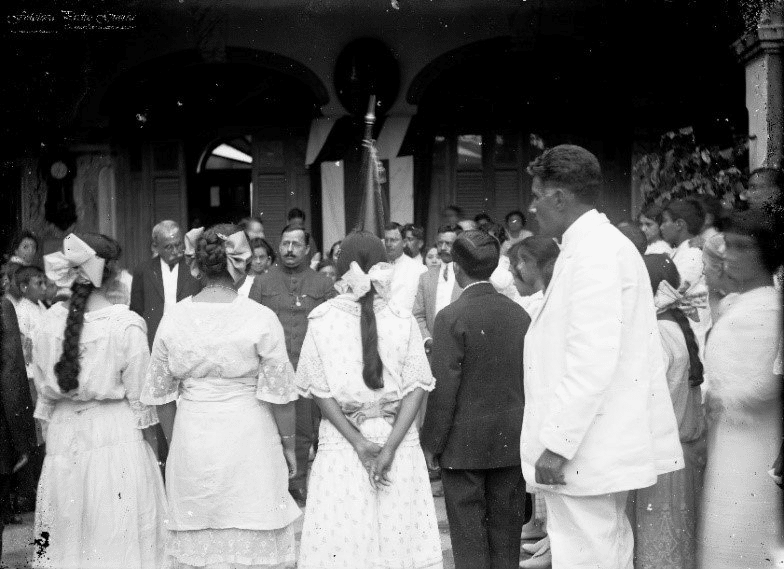

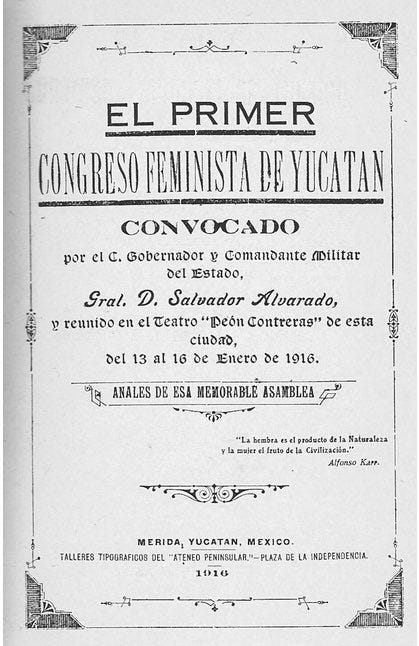

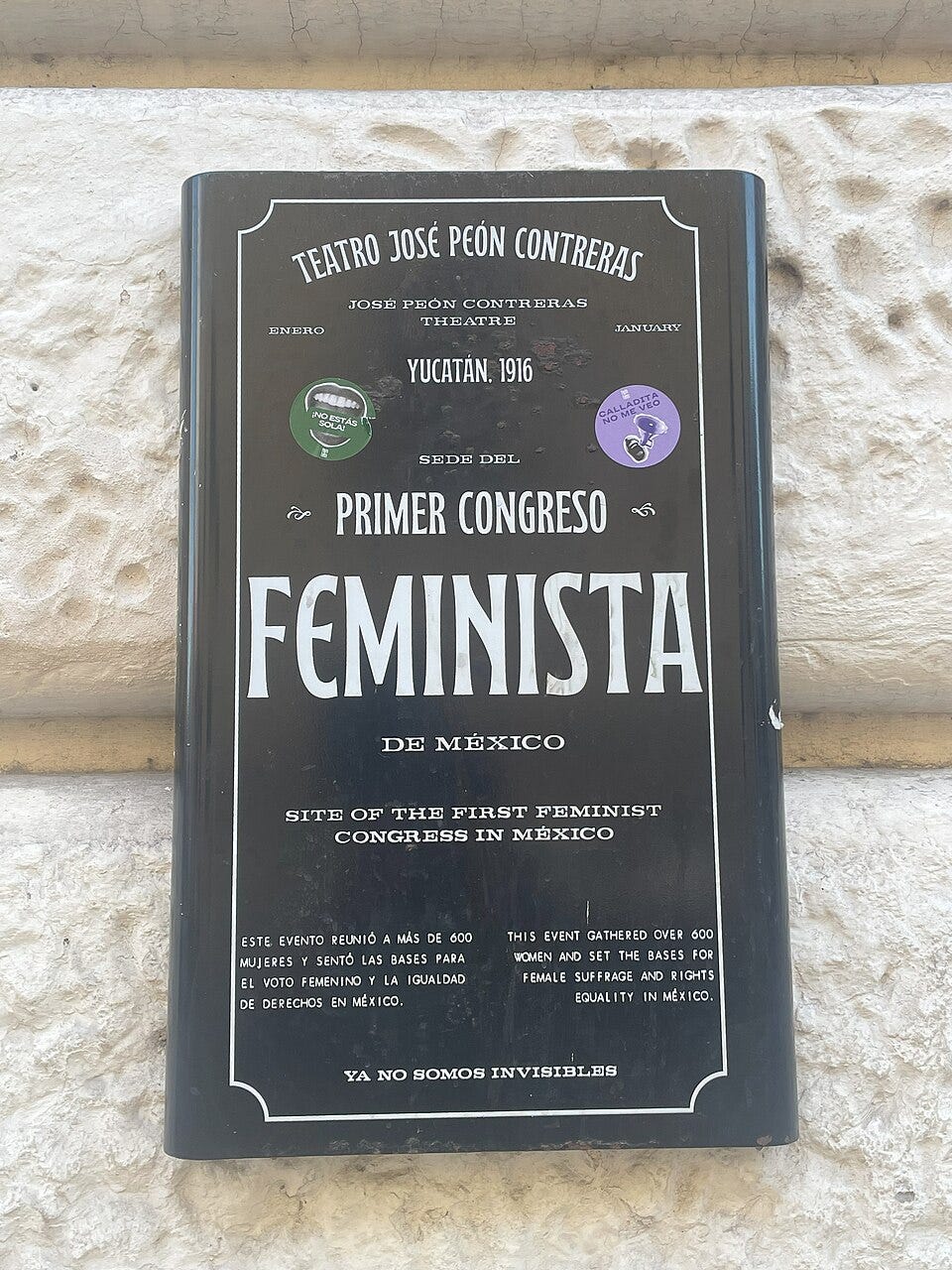

In January 1916, in Mérida, Yucatán, hundreds of women packed the Teatro Peón Contreras for what the Library of Congress describes as Mexico’s First Feminist Congress, held in the middle of the Mexican Revolution. The gathering drew 620 delegates, many of them schoolteachers, and the state government helped make their attendance possible with train tickets, leave time, and pesos.

And from day one, it proved something we still wrestle with now: women can agree that the world is unfair, and still clash hard on what liberation should look like.

Yucatán was already a feminist laboratory, even before 1916

The First Feminist Congress did not appear out of nowhere.

Feminist thought and liberal and radical ideas had built momentum since the late nineteenth century, and the congresses unfolded against the backdrop of the Mexican Revolution.

The congress did not ask women to politely “wait their turn” until the country stabilized. It treated women’s rights as part of the revolutionary project itself, even as the political establishment often framed it through its own agenda.

How the First Feminist Congress came together, and who it centered

The congress convened under the leadership of Salvador Alvarado in Mérida and attracted 620 delegates. The majority of the women who attended were schoolteachers.

However, there was a key structural detail: literacy requirements shaped who could walk into the room, and the attendee base skewed toward middle-class schoolteachers.

So yes, the Congress cracked open the conversation. At the same time, it achieved its “historic first” through a gate that many women, especially indigenous women, could not cross.

The paper that detonated the room

Every movement has a moment that forces everyone to reveal their real comfort levels. In Mérida, it came through a text.

Hermila Galindo put forward a radical reform proposal, and when “La Mujer en el Porvenir” was read aloud, the crowd's reaction swung from approval to shock because it supported sex education, divorce, and secularity.

That reaction tells you everything about the pressure points inside early twentieth-century feminism in Mexico. Many delegates wanted expanded rights, better schooling, and legal reforms. But the moment the conversation touched women’s sexuality and the social order that controlled it, the room turned into a battlefield.

Education, work, and the problem of “respectability”

After the controversy, the Congress did not magically unify. It argued.

Education became a central theme. Delegates disagreed about what education should prioritize and how women should understand their roles as mothers, educators, and public actors. They also debated the Catholic Church and its influence, with some delegates criticizing it as part of the “yoke of tradition” and others defending it as a moral compass.

Still, even with those fractures, the congress treated women’s access to knowledge and work as urgent. It framed women’s education as a route to autonomy rather than a decorative finishing school for “better wives.”

And that is where the respectability politics show up, loud and clear: the same society that limited women’s options often defined “acceptable” women as the only ones worthy of rights.

What the First Feminist Congress won on paper, and what it triggered in law

It is easy to dismiss early feminist gatherings as symbolic, like they were just speeches and photographs.

But the paper trail persisted.

One major result in the post-congress atmosphere was President Venustiano Carranza’s 1917 Law on Family Affairs (Domestic Relations), which expanded married women’s rights compared with earlier legislation.

The congresses criticized the 1884 Civil Code’s denial of married women’s legal and property rights, and that critique influenced Carranza’s decision to enact the 1917 Law of Family Relations, expanding women’s legal rights.

So while not every demand landed immediately, the Congress helped push women’s legal personhood into the realm of state reform rather than private pleading.

A second congress, fewer women, and the backlash you can almost predict

Movements rarely move in a straight line. They surge, then they get punished for surging.

Alvarado called for a second congress in late 1916, but fewer than half the women returned, and the gathering could not secure enough political support for women’s suffrage.

Similarly, even though women’s suffrage remained far off, the debates gave voice to the concerns of middle-class women in early twentieth-century Mexico.

In other words, the First Feminist Congress forced women’s rights into public conversation, and the backlash arrived quickly, through institutional resistance, internal division, and the limits of who society allowed to represent “women” in the first place.

Latinas lead the way, but the record still shows who got left behind

The full version of this story asks harder questions. Who counts as “the women” when a state calls a feminist congress? Who gets to speak, who gets quoted, and who gets remembered. And who gets framed as someone else’s “project” instead of a political subject in her own right.

Even so, the legacy is real. Yucatán’s feminist history keeps resurfacing because it created an early blueprint for organizing, debating, and demanding power. As Yucatán Magazine puts it, the state became a pioneering region where feminist initiatives took root early, including the 1916 congresses, and later milestones such as Yucatán becoming the first state in Mexico to grant women the right to vote and run for office in 1923.

In the end, Latinas (at least, White ones) did not wait for permission to enter politics. They entered, argued, splintered, rejoined, drafted demands, and pushed the law forward anyway.

And if that sounds familiar, it should.