When Resisting Whiteness in the Workplace Becomes a Problem for Latinas

I know all too well the feeling of being looked at under a magnifying glass—especially as a brown Latina in the professional world. Mediocrity was never an option for me. After all, as Latines, we are told to seek excellence and validation from jobs and people in power to make it—even if we have to work twice as hard, code-switch, and downplay our personality and identity in the process.

Workplaces and institutions in this country call us to model behaviors and attributes different from our own as Black, brown, Indigenous, and people of color. If we want to succeed and be accepted in the workplace, we practice professionalism through a set of standards by which we are measured. And that standard is whiteness.

Have you ever used your white voice at work? I know I have.

Writer and attorney Leah Goodridge argues that professionalism is a racial construct. It measures our communication style, interpersonal skills, appearance, and how well we conform to the standards of a job and field.

In professionalism—also under the umbrella of respectability politics—our behavior is measured by our proximity to whiteness throughout places rooted in colonial systems and thinking, and this is the DNA and heartbeat of America.

Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodríguez shares this in For Brown Girls with Sharp Edges and Tender Hearts: “American society dictates that whiteness, and proximity to whiteness, was always going to be a measure of success.”

What more than to see this play out in the workplace as we are assessed by our appearance, presentation, speech, and demeanor as Latinas?

We are measured by our level of perfection—by how well we do our job and carry ourselves with a pleasing attitude, compliant and collected, even while working in hostile spaces toward our bodies.

I had the hardest reckoning of this in the last year while working at a predominantly white and self-proclaimed “progressive” national organization. No matter how well I performed my job and how readily available I was to its work’s demands, I was often scrutinized and micromanaged.

I was tone policed, offending my white colleagues with my communication style as a Latina. Eventually, they told me I did not fit in the work culture that ran off of condescension and institutional racism towards women of color.

I came into this job representing everything it was not: an L.A.-born and raised Latina with the cadence of her Central American mother–confident, sharp, clear, and assertive in communicating and expressing her needs within the workplace openly. This way of being and working within white supremacy is a threat and does not fit well within the professionalism white people practice and set as the standard.

Latinas in the workplace are often told we are too much, too loud, too “fiery,” too angry, and unacceptable when being ourselves. We are villainized when sharing vulnerabilities and rarely humanized.

During meetings at this job, white women would look at me as if I had the audacity to take up space, speaking so confidently by knowing what I was talking about in our marketing field.

At times, they would squirm, look startled, or interrupt me while I spoke directly to them. My White passing Latina boss behaved the same, especially in conflict, and became a product of this system. She once approached me with concern, telling me I needed to be more pleasant and softer in order to be liked by our white colleagues if I wanted to succeed in my job.

According to her, I needed to get on white people’s good side and overextend myself to an ultra level of perfection for their approval for them to take me seriously even though the workplace set people of color up to fail.

These same white women humiliated Black and brown women on my team publicly. They would share and catastrophize minor flaws in our writing, designs, and messaging for campaigns, masking their actions as “wanting what was best” for us. They wouldn’t even dare to address us directly, at an eye level, and with respect.

Places rooted in white supremacy function thinking they know better, speak better, work better, and are better than the worlds we come from.

Women of color are required to submit to this toxic work behavior in the name of professionalism. We are expected to hold the brunt of microaggressive and dehumanizing actions in the workplace, to withstand, bite our tongue, and remain calm and “professional” because whiteness calls us into passivity and silence.

During my exit interview before my last day, my boss remained stoic while sharing, “I know you had a hard time adjusting here,” which was really code for “I know you couldn’t embody whiteness and endure.”

I was problematic the moment I arrived and showed up as myself. I was problematic the moment I resisted micromanagement, perfectionism, and the pressure to please white women and make them comfortable at my job.

When I spoke out against workplace dysfunction and systemic racism to my supervisor, I came into question for appearing “defensive,” difficult, and not collaborative enough.

My facial expressions, eyebrows, and tone were policed whenever I reacted to white people acting out in their power. I could not fit in and questioned the very system that made my job impossible. This was my reality, that I became difficult to work with, unfit for the job and workplace, and problematic whenever I interrupted, interrogated, and resisted whiteness.

My authenticity, my concerns, and my vulnerability under this professional white gaze could not exist and take up space, but those of white people always did.

God forbid I, a Latina was showing up fully and human.

This was not my first rodeo with professionalism and respectability politics in the workplace. However, it was the most consistent and ongoing struggle that affected me and the Black and brown women I worked with.

I didn’t want to grow another layer of skin to endure. I wanted these places to change and be held accountable. I think about how easily we demonize Latinas who speak up, resist, and choose to show up as we are, away from whiteness. How success looks like shrinking, caving in, becoming smaller and more digestible versions of ourselves to be allowed in and to stay.

Yet, no place is worth making us feel small or questioning our identity, contributions, and dignity. Spaces and institutions built on colonial systems are no places for us to thrive.

These days, I am writing my truth and sharing space with other Latinas and women of color who have felt misunderstood, misrepresented, and who also carry the label of “difficult.”

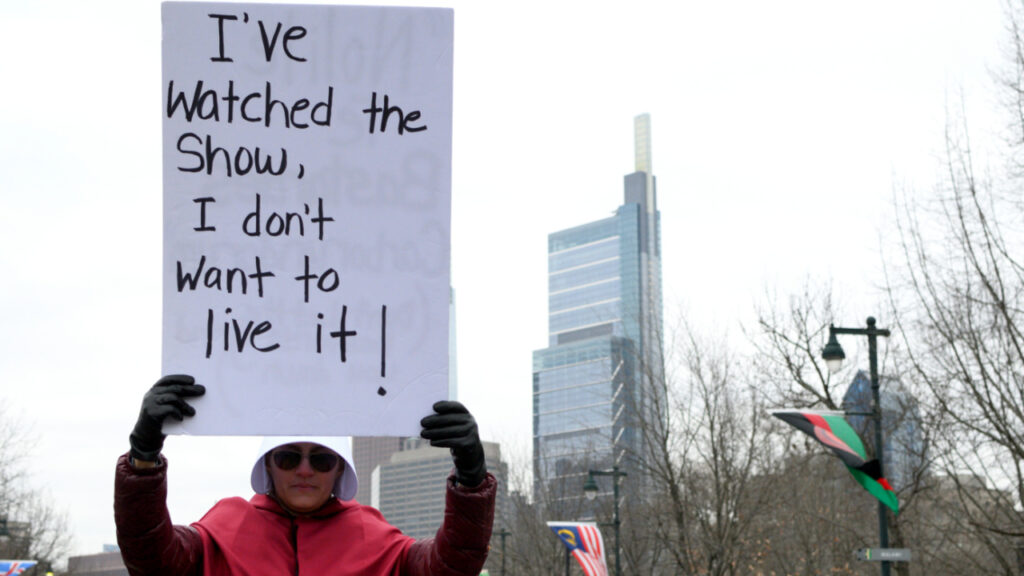

We are not alone and not being too much. We resist. We resist by loosening our tongues. We resist talking back, and we resist in our questioning of systems. With silver hoops in our ears, red pigmentation on our lips, and a gel x set of nails, we resist in the ways we show up and take space. We resist through the wit and thunder of women in our lineage who went before us. We resist whiteness and what it deems appropriate for us. We resist and choose to thrive.

Heidi Elizabeth Lepe (she/her) is a proud “Chicana Central Americana” writer, theologian, and community advocate based in West Los Angeles. The daughter of a Catracha mother and Mexican father, Heidi embraces her dual heritage unapologetically, weaving her cultural roots into her work. As the founder of Brown Beloved Co., she is dedicated to uplifting the Latine community at the intersection of faith, cultural roots, and justice. Inspired by her immigrant upbringing, local leaders, and thinkers like Gloria Anzaldúa and Bell Hooks, Heidi writes with a focus on healing, liberation, and the flourishing of marginalized voices.