Why María Félix Chose Women Artists Over Diego Rivera, and What She Did to His Painting

Everyone wanted to be painted by Diego Rivera. Except María Félix. This is the story of the one painting La Doña could never stand. And the reason? The male gaze.

She once described it as a vulgar attempt at capturing her beauty. A caricature, not a portrait. According to an interview María gave to journalist Jacobo Zabludovsky, it marked the end of her friendship with Rivera. And yet, that infamous 11 x 15.6 cm painting, which vanished after Juan Gabriel’s death, continues to haunt the art world.

Let’s unravel what really happened and why María Félix always preferred the brushstrokes of women.

When Diego Rivera painted María Félix, she hated it

In 1949, Diego Rivera completed a portrait of María Félix that he was clearly proud of. She wasn’t. According to Infobae, María “hated it with all her heart” the moment she saw it. She had asked Diego to paint her as a Tehuana, a reference to her cultural pride. Rivera refused. “He said it was too vulgar and he didn’t want to. So he painted me the way he wanted,” the actress said.

Instead, Rivera painted her in lace, with her chest exposed. María was furious. She had a bricklayer paint over parts of the work with white paint to conceal what Rivera had revealed. For a while, she hung the modified painting in her living room. Rivera never knew.

According to Infobae, Rivera had wanted to exhibit the work, but María refused. That disagreement led to a fallout between the two. Rivera didn’t speak to her for a year.

What happened to Diego Rivera’s lost portrait of María Félix?

Eventually, María and her husband, Alexander Berger, sold the painting. First, it was supposed to go to Dr. José Álvarez Amézquita. But it was Juan Gabriel who bought it in the 1970s for 15 million pesos. He was a devoted admirer of La Doña and even composed “María de todas las Marías” in her honor, comparing her to the Virgin of Guadalupe.

According to Rossy Miller, daughter of Lucha Villa, the portrait was last seen at Juan Gabriel’s Las Vegas home. After his death, the painting disappeared. Some believe it was sold on the black market. Others think it passed to his son and heir, Iván Gabriel. In 2020, the singer’s lawyer, Guillermo Pous, suggested that former governor César Duarte might have it. To this day, its whereabouts remain unknown.

Why María Félix said women understood her better

While Diego Rivera’s painting left a bitter mark, María Félix found comfort in the work of women artists. According to an in-depth study by scholar Dina Comisarenco in Reflexiones Marginales, María developed close friendships with surrealist painters like Leonor Fini, Bridget Bate Tichenor, Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, and Sylvia Pardo.

She said it herself: her personality had “been better understood by women.” These artists didn’t focus on motherhood, sensuality, or beauty. They painted her emotional depth, her strength, and her complexity.

The surrealist portraits that María Félix actually loved

After the death of her husband, Jorge Negrete, María Félix fell into a depression. That’s when she sought out Leonor Fini, who painted three portraits of her: Reina del sol, Las dos Marías, and Detrás de la puerta. In Reina del Sol, Félix is framed by light: “It expresses the inner strength that sustains my existence,” she said. “Behind the stormy clouds, the Sun outlines my features, showing my will to defeat adversity.”

Bridget Bate Tichenor also painted her in Domadora de quimeras. In it, María caresses a mythical feline, her face serene and contemplative. “She painted me in a contemplative, reflective attitude, which is very much part of my nature, especially when I’m preparing the lead role in a movie,” said María.

Remedios Varo created Astro errante, which didn’t include her face, but María insisted it was still about her. A woman in the painting leaves a trail of light across a grey sky, wearing moons on her feet, pulled through the air by a kite among diamonds and tears. For María, it was a symbolic self-portrait.

María Félix replaced Diego Rivera’s painting with one by Leonora Carrington

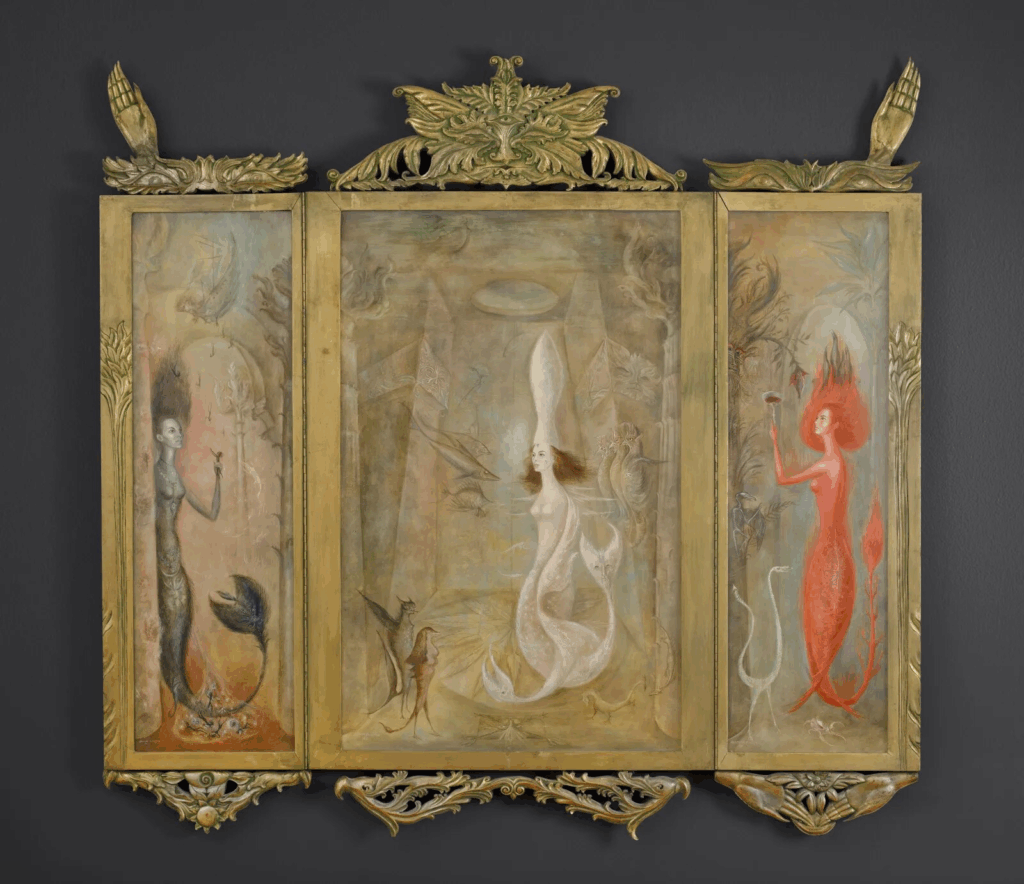

Leonora Carrington painted María’s dream, literally. In Sueño de sirenas, María becomes a siren of nacre, then fire, then black charcoal. “I was in the sea and I was a nacre mermaid. Then I reached these divine beaches and became a fire mermaid… I went into the sea and instead of coming out wet, I emerged in flames,” she told Carrington. She called the triptych “hermosísima.”

Later, Carrington painted La maja del tarot to replace Rivera’s work, which María “no longer wanted in her house.” The painting depicts her floating in an ancient temple, dressed in symbols of the tarot and crowned with the moon and a scarab beetle. Carrington included one unusual detail: a fuzzy kite-shaped creature emerging from María’s cloak. “That figure represents the ‘bad blood’ leaving my body,” María said. “I’ve always thanked Leonora for that.”

The final portraits of María Félix showed her as a queen and a myth

In the 1970s, Sylvia Pardo painted María in Las tres Marías and Nuestra señora del Apocalipsis, blending religious iconography and feminist symbolism. In Las tres Marías, Pardo portrays her as a vampira, a witch in flight, and a regal equestrian draped in silk. One side of the folding screen glows with gold and color. The other is stark black on gold, evoking medieval sacred art.

According to Comisarenco, María loved this piece and kept it in her Polanco home for years. Though some critics objected to the sensual religious symbolism, María never flinched.

In Nuestra señora del Apocalipsis, Pardo drew from the Book of Revelation. María stands dressed in light, crowned with stars, facing a dragon. The painting could be read as a metaphor for motherhood, for resistance, or even for María’s personal battles. As Comisarenco notes, the symbolic richness of these works “made possible a representation closer to the life, aspirations, and vital energy of the actress.”

María Félix turned portraiture into a feminist act

Throughout her life, María Félix used art as a way to reclaim her image. She had been cast in dozens of roles that embodied tired gender tropes: the good woman, the vamp, the seductress. But as Comisarenco writes, María wasn’t just a muse. She commissioned portraits as a strategy of resistance, art that allowed her to create a new mythology of herself.

She was a woman who, in the words of Octavio Paz, had “the audacity not to conform to the idea men have made of women.” Through surrealist brushstrokes and allegorical depictions, she told her own story. And she chose women to tell it with her.