All the Times Rita Moreno Stood Up for What’s Right

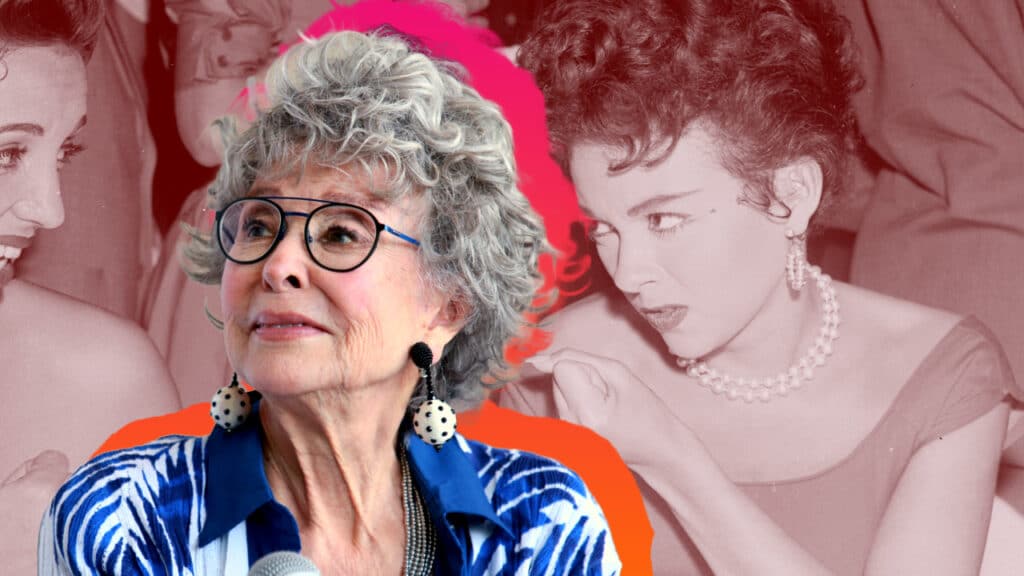

Rita Moreno’s story begins far from Washington. She was born Rosa Dolores Alverío in Humacao, Puerto Rico, in 1931 and spent her early years on a farm near Juncos. Her mother, Rosa, saved enough money to bring her to New York at 5 years old, leaving her baby brother, Francisco, behind. Moreno later called that her first heartbreak.

In New York, she started dance classes and found work fast. By 11, she recorded Spanish-language versions of American films. At 13, she landed on Broadway in Skydrift as “Angelina,” a role that caught Hollywood’s eye, the museum’s profile notes. Louis B. Mayer signed her to a contract with MGM. She took her stepfather’s surname and became Rita Moreno.

Hollywood did not embrace her as a girl from Juncos. It embraced her as “the dusky maiden.” According to her own accounts, she played a Cajun girl in The Toast of New Orleans, a Tahitian girl in Pagan Love Song, an enslaved Burmese woman in The King and I, and a string of “dusky damsels” at 20th Century Fox.

“I wanted to be a movie star,” she told The New York Times. “But I never imagined that it would be so hard, and so painful. Never. Never.”

She has spoken about being raped by her agent as a young actor, and about how little she thought of herself at the time. In the documentary, “Rita Moreno: Just A Girl Who Decided To Go For It,” she describes staying with that agent “because he was the only one who was helping me, in my so-called career.”

The activism comes out of that wound, out of being told again and again that she was exotic, replaceable, and lucky to be there.

So when Harry Belafonte called and asked her to fly to Washington in 1963, she said yes, even though she knew it could cost her work.

“It took a lot of courage and conviction for us to show up,” she later said, remembering that many stars worried they would lose their jobs. “And that’s what I want us all to remember, is to show up, in spite of.”

The day the March on Washington changed everything

Moreno calls August 28, 1963, the day she became an activist.

“My first major experience was on the March on Washington when I sat no less than 15 feet from Dr. Martin Luther King,” she says in the PBS documentary. “I was there when he uttered the I Had a Dream speech.”

She remembers the heat and remembers looking out at a “sea of faces that traveled from all over the world to be a part of creating change.” She remembers that Dr. King and the Civil Rights Movement were not popular. “There were a lot of frightened people out there who were afraid of change,” she notes.

Moreno knew she already had “enough trouble” in Hollywood as the woman who got “Spanish spitfire” roles. She still went. On the plane to Washington, she watched James Garner “downing bottles of Pepto-Bismol because he had a stomach ulcer from all the fear,” she recalled. She admired him forever because he came anyway.

At the march, she listened as King spoke about “the unspeakable horrors of police brutality.” Then she spoke too. In the documentary, we can see archive footage of her addressing “the Negro kids, the Puerto Rican kids, the Chinese kids, to every nationality,” and telling them: “listen to this. Wear your nationality like a flag. Be proud of it. Be proud, Puerto Rican people.”

For a girl who once let other people define her face and her name, that public call to pride becomes a turning point.

“Hope is in my DNA,” she wrote for the Television Academy. “We came to the United States by boat when I was just five years old. Hope and resilience are in my nature. I will always keep fighting for what’s right.”

Rita Moreno carries civil rights into Hollywood

After West Side Story in 1961, Hollywood gave Moreno an Oscar and then tried to push her back into the same narrow frame.

She won Best Supporting Actress for her role as Anita. She became the first Latina to win an Academy Award. According to the National Women’s History Museum, even with that Oscar, agents still offered “exotic” roles and stereotypical Latinas. She decided to walk away and spent seven years mostly doing theater in New York and London.

That decision reads as quiet activism. A refusal to keep feeding a system that wanted her as background color.

“I was always offered the stereotypical Latina roles,” she later said. “The Conchitas and Lolitas in westerns. I was always barefoot. It was humiliating, embarrassing stuff.”

When she came back in the 1970s, she chose projects that gave her agency. She joined The Electric Company and shouted “Hey, you guys!” at a generation of kids. Later on, she won a Grammy for the show’s album. She played Googie Gomez in The Ritz and won a Tony. She became one of the first performers to reach EGOT status.

But she never let the trophies erase the damage. Even in West Side Story, she pushed back. She told The New York Times that makeup artists painted all the Puerto Rican characters the same muddy color. When she objected, the makeup artist suggested she was racist.

Into her 60s, she says, she still received stereotypical offers. Even in the past few years, she described being “diminished” at a “high-caliber professional occasion” and going home to “weep for three days,” according to the Times.

Her activism grows out of that ongoing abrasion. As she wrote: “When you’ve been ignored for so long, you feel that no one can hear you and no one cares. But we must speak up and remain hopeful and unafraid.”

Standing up for Latinas on screen and off

Moreno’s activism takes shape in the roles she fights for, and in the industry she keeps calling out.

She wrote: “It’s astonishing to me to see how little progress the Hispanic community has made,” especially in Los Angeles, where Latinos make up a huge part of the population. “It’s hurtful that there is still not much representation in front of or behind the camera.”

She pointed to One Day at a Time and said, “My show, One Day at a Time, is the only Latino show on the air. I don’t get it; I don’t understand it. It’s shocking and enraging.”

She insists on unity. “We are Mexican, Puerto Rican, Argentinian, Cuban, Colombian – and so much more,” she wrote. “Irrespective of our nationality, we must stick together the way I’ve seen other communities of color do.”

In the PBS documentary, she appears with Representative Jackie Speier in a shop, staring at two teddy bears from the same company. One is blue. One is pink. The pink one costs three dollars more.

“Because it’s a girl?” Moreno asks. “Are you serious?”

Speier explains that she is working on a bill for National Women’s History Month that “is going to repeal the gender tax. It’s a pink tax repeal act.” Moreno wants to see more of these items. The scene feels small and domestic. It sits right beside her memory of King’s speech.

Her advocacy travels outward, too. According to HarperCollins’s profile of her, she has spoken out for racial and gender equality, childhood education, immigrant families, and relief for Puerto Rico. At the Ellis Island Medal of Honor ceremony in 2018, she said:

“I do believe, with all of my heart and soul, that yearning masses will always huddle on the border of hope. And I pray that America will always be that beacon of those people’s dream.”

She has also used her voice in electoral politics. In her Television Academy piece, she writes, “I’m very active and on one of the committees for the Joe Biden campaign.” She imagines the impact if the Hispanic vote showed up in full.

“There is so much hatred and vehemence coming from the White House, and enough is enough,” she wrote, referring to the Trump administration. “We must make our voices heard not just in Hollywood but in all sectors.”

Rita Moreno keeps fighting for her community

Moreno’s activism is not perfectly smooth. It never pretends to be.

In 2021, she went on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert and defended her friend Lin-Manuel Miranda when people criticized In the Heights for colorism. “I’m simply saying, ‘Can’t you just wait a while and leave it alone?’” she said on air.

A day later, she walked back those comments. “I didn’t realize that while I was defending him, I was ignoring a very important question,” she told The New York Times. She called her response “insensitive.”

Director Mariem Pérez Riera told the Times that Moreno “comes from a different generation,” yet “every day she tries.” Sometimes she gets it wrong. She listens anyway.

The throughline is a stubborn presence. She shows up at marches, in writers’ rooms, and on sets. Rita Moreno shows up at fund-raisers and on campaign committees. She shows up as Lydia in One Day at a Time and as Valentina in Steven Spielberg’s West Side Story, bringing a lifetime of experience into a new version of the story that once painted her face “the color of mud,” as she told the Times.

She also shows up at home. In the Peabody Career Achievement Award clip, she dedicates the honor to her mother, Rosa, who worked as a sweatshop seamstress to pay for rent and dance lessons. “My fame is her fame,” she said. “Therefore, this beautiful, precious honor is also in her honor.”

At 93, she still calls herself “single” and “independent” in interviews. “I love being by myself,” she told the Times. “It’s not hard to be alone. In fact, it’s great if you like the person you live with.”

The person she lives with carries the girl who sat 15 feet from Dr. King. The woman who told kids to wear their nationality like a flag. The performer who slithered across a piano at a fundraiser and made a room of politicians blush, as Jackie Speier likes to remember.

“I will always keep fighting for what’s right,” Moreno wrote. It reads less like a promise and more like muscle memory.