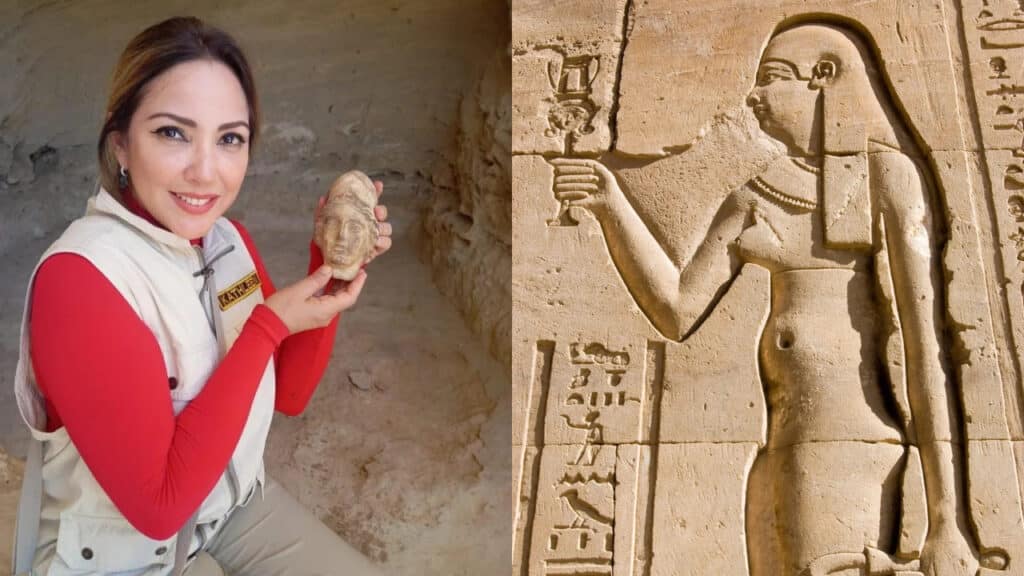

Did a Latina Just Crack the Biggest Archaeological Mystery of Our Time? The Search for Cleopatra’s Tomb Heats Up

If Cleopatra really whispered a prophecy that a woman would one day find her tomb, she probably did not picture a Dominican criminal lawyer in a hard hat, brushing sand off hieroglyphs.

Yet that is exactly who has spent twenty years chasing the queen’s final secret.

Dr. Kathleen Martínez grew up in Santo Domingo reading about Egypt in her father’s legal library. Her parents pushed her toward a “serious” career, so she became a lawyer and later earned a master’s degree in finance and archaeology. She opened a law practice, then kept studying Cleopatra on her own time.

In a 2016 PBS Q&A, Martínez said she dedicated “15 years to study Cleopatra as a historical character” and became obsessed with “the mystery of her last days.” She treated Cleopatra’s death like a legal case, tracking “life, death, friends, enemies, and projects” through ancient texts to figure out where the queen chose to be buried.

That case has now led her to an ancient temple complex, a hidden tunnel, and a sunken port off Egypt’s Mediterranean coast. Each new find tightens her focus on one question that has haunted archaeology for decades.

Where is Cleopatra’s tomb, and could a Latina be the one who finds it?

Why Kathleen Martínez believes Cleopatra’s tomb lies at Taposiris Magna

Most historians still believe Cleopatra rests in the royal cemetery in Alexandria. Several experts told CNN that literary sources place her tomb in the city’s royal quarter, which lies beneath the modern coastline after centuries of earthquakes, land subsidence, and sea-level rise.

Martínez sees something different in the record.

She argues that Cleopatra, who aligned herself with the goddess Isis, would have chosen a temple of Isis near Alexandria as a safer, more symbolic resting place. According to PBS and her own published account, she studied Strabo’s descriptions of ancient Egypt and mapped 21 sites linked to the Isis and Osiris myth. She then ruled out locations that felt too small or did not center on Isis.

One temple remained. Taposiris Magna, west of Alexandria, near today’s town of Borg El Arab.

When she visited Egypt for the first time in 2002 and walked through the semi-ruined temple, she “understood that it was the place she was looking for,” she later told PBS. Egyptian authorities had seen Taposiris Magna as incomplete and insignificant. To Martínez, the site looked ravaged and buried under centuries of sand.

She returned to the Dominican Republic, secured support from Universidad Católica Santo Domingo, and in 2004 obtained a license to excavate. She financed the early seasons herself.

Within a year, her team uncovered a blue glass foundation plate etched with Greek and hieroglyphic inscriptions, confirming that the temple belonged to Isis. They later found hundreds of bronze coins bearing Cleopatra’s name and likeness, along with statues, a stele dating the temple to the Ptolemaic period, and a large burial ground from the same era, according to reports from Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities and coverage in National Geographic.

For Martínez, every artifact pointed to the same conclusion. Taposiris Magna held a deep connection to Cleopatra’s world, and perhaps to her death.

The tunnel, the sea, and a sunken port tied to Cleopatra’s tomb

The search took a dramatic turn underground and underwater.

In 2022, Martínez’s team used ground-penetrating radar at Taposiris Magna and located a tunnel about 43 feet under the temple, according to Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. The structure stretched for roughly 4,281 feet. It ran in the direction of the Mediterranean Sea.

That raised a new possibility. If the tunnel extended beyond the shoreline that existed in Cleopatra’s time, what waited offshore?

Martínez contacted oceanographer Robert Ballard, the National Geographic Explorer best known for finding the Titanic. In the documentary “Cleopatra’s Final Secret,” Ballard says, “I’ve been doing this for 50 years. I’ve been underwater. I’ve never seen anything like this. This clearly looks like it’s man-made.”

Together with a team of underwater archaeologists, they surveyed the seafloor near Borg El Arab. They uncovered:

- Rows of towering structures that may have been columns over 20 feet high

- Polished stone floors

- Cemented blocks

- Multiple ship anchors

- Tall storage jars called amphorae

Researchers dated the remains to Cleopatra’s lifetime. Egypt’s antiquities ministry announced that the finds pointed to a previously unknown ancient port linked to Taposiris Magna. Mapping showed that the ancient coastline lies several kilometres seaward of the modern shore, consistent with the location of the submerged features.

Martínez now believes Cleopatra’s body left Alexandria for Taposiris Magna after her death, then traveled through the underground tunnel to this offshore harbor. From there, priests may have ferried the queen and her lover, Mark Antony, to a secret burial site away from Roman reach.

“The discovery of the tomb of Cleopatra will be one of the biggest discoveries of the century,” she told CNN. She added that Egyptian tombs let the dead speak, and that Cleopatra’s burial “should have all this important information that she wanted us to know about her, about her time, about the way she thinks.”

The long game and how a Latina keeps pushing toward Cleopatra’s tomb

Martínez has lived in Egypt for years and leads the Egyptian Dominican mission at Taposiris Magna. She also serves as minister counselor for cultural affairs at the Dominican embassy in Egypt, according to her biography.

Her path never followed a straight academic line. She started as a criminal lawyer, ran a legal practice, and then slowly shifted her life toward archaeology. In the PBS Q&A, she recalled parents who warned her she would “never have a serious job” as an archaeologist and urged her to study law instead.

She listened at first. Then she created her own route.

She still handles a small number of legal cases. “Sometimes I will be inside a subterranean chamber and a client will call me for a consultation,” she told PBS. “It is a strange sensation.”

Her archaeological work has faced skepticism, funding hurdles, and political instability. She has said that looting and destruction after the Arab Spring created new risks for sites and artifacts. Major figures in Egyptology also doubt her central hypothesis.

Former antiquities chief Zahi Hawass wrote in Al Ahram that he does not believe Cleopatra lies at Taposiris Magna and argued that Egyptians did not bury rulers inside temples dedicated to gods. Other scholars told CNN that ancient writers placed Cleopatra’s tomb in Alexandria, near her private palace port.

Martínez responds by keeping her focus on the dig. “I choose to dedicate my time to the contributions rather than the critiques,” she said in the PBS interview. She frames her finds as data that helps scholars “better comprehend an important historical period, much of which remains a mystery.”

Why experts still debate the trail that leads to Cleopatra’s tomb

The new underwater discoveries have sharpened the debate rather than ended it.

Supporters of Martínez’s theory see the tunnel and the port as strong circumstantial evidence. The temple honors Isis, and the artifacts date to Cleopatra’s era. Hundreds of coins with the queen’s face turned up at the site. The tunnel connects the sanctuary to a harbor that no ancient text mentioned.

The inscription of a pilgrim who thanked Osiris and Isis for surviving a sea storm near the site suggests that worshipers moved between the temple and the coast. That fits Martínez’s idea of a ritual route that could also carry a royal body.

Skeptics want more proof.

Cambridge historian Paul Cartledge told CNN he believes Augustus wanted Cleopatra buried in Alexandria’s royal cemetery. He argued that the first Roman emperor used her tomb and his control of it to present himself and Rome as “the legitimate, direct successors of the Pharaohs.” Other specialists argue that they need peer-reviewed publications from the Taposiris Magna mission before they can evaluate all of the claims.

So far, no inscription has surfaced that clearly names a structure as Cleopatra’s tomb. No sarcophagus with her name has appeared. Even some statue identifications remain contested. Egypt’s antiquities ministry said in a statement that the female statue Martínez identified as Cleopatra is more likely to depict another royal woman.

The mystery keeps the argument alive. It also keeps funding and attention flowing to a Latina-led excavation that many people once dismissed.

How Cleopatra’s tomb search rewrites who gets to tell ancient stories

Behind the technical details lies something deeply cultural.

For centuries, European scholars and institutions dominated Egyptology. Museums in London, Paris, Berlin, and Rome are filled with carved sarcophagi and gilded funerary masks taken from Egyptian soil. Narratives about Cleopatra’s life were filtered through Roman writers, who portrayed her as a dangerous foreign seductress rather than as a political thinker or scholar.

Martínez comes from a different world. She grew up in the Caribbean in a family shaped by Dominican, Franco, and English roots. Martínez studied law because that was how a working professional survived in her context. She entered Egyptology without the backing of a European university.

In 2018, the Cairo Museum opened an exhibition titled “10 Years of Dominican Archaeology in Egypt” to showcase more than 350 artifacts that the mission discovered from the Ptolemaic period. Egyptian authorities highlighted the show as the first significant contribution from Latin America to the discipline.

Her story hits differently for Latinas who grew up hearing that archaeology, diplomacy, or Egypt in general belonged to someone else.

If a Latina finds Cleopatra’s tomb, the message goes far beyond Egypt

No one knows if the next excavation season at Taposiris Magna will reveal Cleopatra’s actual resting place. Even the most passionate defenders of Martínez’s theory admit that the tomb could still lie under the submerged royal quarter of Alexandria or in an as-yet unknown location.

What we do know is this: A Dominican woman who once argued legal cases in Santo Domingo now leads dives off Egypt’s Mediterranean coast with the scientist who found the Titanic. She traces hieroglyphs with her fingertips and follows tunnels carved two thousand years ago. She reads myth, law, and propaganda and then tests those texts in soil and stone.

In interviews, Martínez often says that archaeology “transcends borders, culture, language, and any socioeconomic divide.” She tells young people that “it is never too late nor too early to become involved,” as long as they bring passion and curiosity.

Some fans like to imagine Cleopatra smiling at the idea that a woman would be the one to piece together her final story. There is no ancient text that confirms such a prophecy. What we do have is a living example.

Between sea and sand, between temple and harbor, between law and archaeology, a Latina refuses to let go of the trail that may lead to Cleopatra’s tomb.