Gaby Acosta Brings Indigenous and Latina Heritage to Emmy-Nominated Costume Design

The first time Gaby Acosta stepped onto a set as a costume designer, she was carrying the weight of two things: her mother’s relentless work ethic and the knowledge that no one in the room looked like her. Born in Tijuana and raised in the U.S. by a single mother who worked as a housekeeper, Acosta had no industry connections. She had determination, talent, and a deep love for storytelling through clothing. That combination would eventually land her an Emmy nomination for Outstanding Period Costumes for Taylor Sheridan’s 1923, the Yellowstone prequel starring Harrison Ford and Helen Mirren.

But as Acosta tells FIERCE, her work on 1923 was not just about period accuracy. It was about functionality, survival, and using costumes to carry Indigenous stories with precision and care.

For Gaby Acosta, period costume design starts with survival

Filming 1923 meant battling both triple-digit Texas heat and bone-chilling cold. According to Acosta, every garment had to look authentic while helping actors withstand extreme conditions. “Climate presented a significant challenge in our daily tasks, from extreme heat to bitter cold,” she says.

Her team found inventive solutions that didn’t break the period illusion. In hot weather, they hid ice packs and cooling vests under costumes. In the cold, they layered in electric thermals and hot packs for gloves and shoes. One Texas shoot required custom alterations for Teonna Rainwater, Runs His Horse, and their stunt doubles. “We tailored costumes by removing sleeves to reduce layers,” Acosta explains. “I am especially proud of how we maintained costume integrity while innovating with hidden compartments for ice packs.”

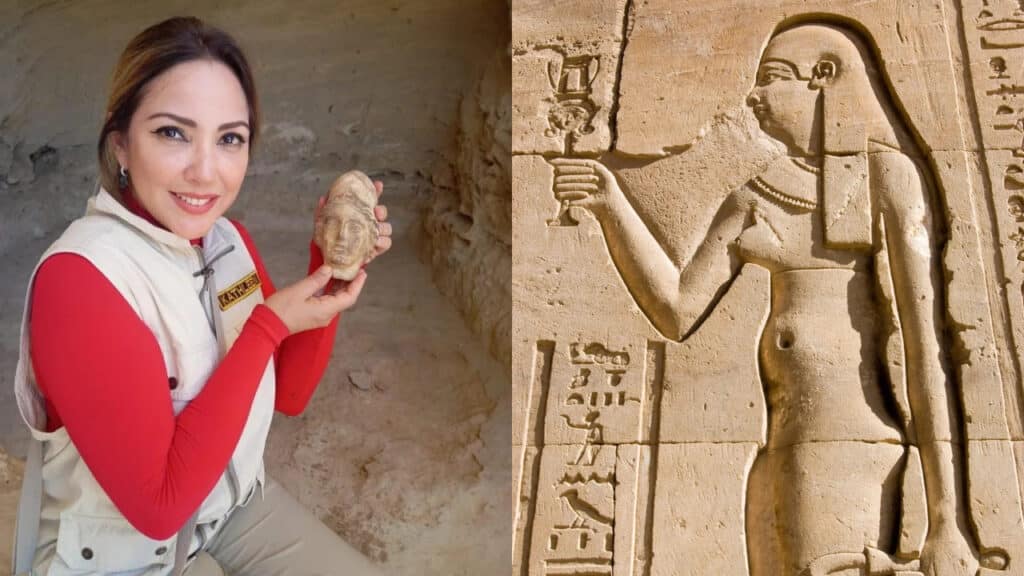

How costume design can tell Indigenous stories

Acosta says 1923’s portrayal of Teonna Rainwater’s storyline called for a balance of historical realism and cultural respect. In 1923, many Native communities had adopted Western silhouettes but still preserved traditional elements.

“It was important to incorporate traditional pieces like beads, feathers, and wool leggings for characters such as Runs His Horse,” she says. The team sourced from Indigenous artists whenever possible. Comanche prop artist Cameron Martinez and his wife crafted a thunderbird neckerchief slide for the character Two Spears. “Including such details made these characters particularly special and showed that traditions were not lost,” Acosta says.

Large-scale costume scenes are all in the details

One of the biggest moments of the season came in Episode 3: a cowboy meetup with more than 25 stunt performers on horseback. For Acosta, individuality mattered as much as authenticity. “During the fittings, we love getting to know the stunt performers and allowing their personalities to shine through,” she says.

Research into popular 1920s hat shapes helped distinguish each cowboy. Even the way a bandana was tied told a story. “The hat makes the cowboy,” Acosta explains. Seeing the final scene play out against Palo Duro Canyon was, in her words, “very satisfying.”

Why Gaby Acosta is opening doors for Latina and Native designers

For Acosta, representation behind the scenes is personal. “As I came up in this industry, I never had the opportunity to work under a Hispanic designer,” she says. That absence fuels her drive to create access for others.

She recently joined LiNC, a Latinos in Costume group, where she’s found a network of talented peers. Acosta actively seeks and hires Latino costumers for her projects. “My hope is to bridge some of the existing gaps in the industry,” she says. “We must not be silenced. We need to speak out, be loud and proud of our presence, and actively help create opportunities for others.”

From building hidden ice pack compartments into 1920s-era coats to commissioning hand-crafted Indigenous accessories, Acosta’s work shows that costume design is as much about advocacy as it is about aesthetics. For her, each project is a chance to honor heritage, amplify underrepresented voices, and prove that authenticity belongs at the center of Hollywood storytelling.