This Latina’s Postpartum Shapewear Brand is Fighting for Maternal Health Equality

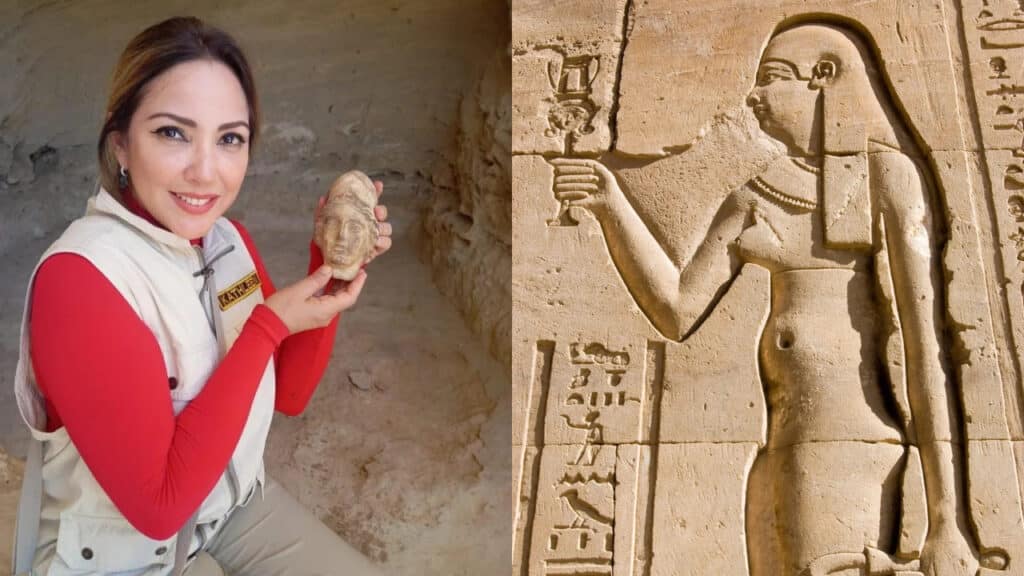

Lizeth Cuara is a self-made entrepreneur whose personal journey led her to launch a transformative brand.

“Misty Phases,” an all-inclusive postpartum recovery brand that aims to raise the standards of postpartum care for all women of color, was born from Cuara’s traumatizing birthing experience. She named the brand after the “fog” that follows childbirth.

“It felt like that whole journey was just a fog, a mist, phase after phase,” she told mitú. “And then with motherhood and having children, everything is just a phase, too. It’s just this big blur.”

Inspiration for the brand struck from all sides. Her mother’s, her own, and that of many women of color who have historically dealt with inequalities in the maternal healthcare system.

Recent data released by the CDC showcases the potential dangers of childbirth and postpartum complications. However, these are highest among women of color.

In 2020, there was a surge in maternal death rates among Latinas, rising from 12.2 to 19.2 in women aged 25 to 39. Cuara experienced these inequities firsthand and took a stand.

Her birth story is nothing short of horrific

She recalls the experience of birthing her daughter, stating, “I was administered the epidural incorrectly, although I didn’t know it at the time. I remember laying there and my brain was so hot — it was on fire. And I remember thinking, ‘This is death. I’m dying.’”

Cuara confessed she felt so sure she was dying that she didn’t even ask for help.

“When I realized I didn’t die, I said to someone, ‘My brain is on fire.’ Obviously, I had questions and concerns, and our questions were completely brushed off,” she revealed. “They didn’t offer an explanation or an apology. Nothing. It was complete silence on their end.”

What followed were weeks and months of agony as Cuara attempted to care for her newborn child and her failing body.

“They just give you this baby, and no instructions on what to do. They didn’t say, ‘Oh, you have stitching down there, we injected you incorrectly so this is what you should expect’… nothing. You have a whole new body. You’re leaking milk, you’re bleeding. I was in so much pain,” she added.

Her health began to decline seriously. She was in so much pain that she could barely walk and only carry her baby with her forearms, not her hands. “I typically weigh around 130 pounds— I was down to 105. I just didn’t know how to care for my body,” she admitted.

She returned to the hospital seeking answers. “I told them, ‘I’m a new mom, I’m not feeling well, I have all these symptoms.’ And I was admitted to the hospital only to be told, ‘You’re just stressed’ and ‘Stop carrying your baby.’”

Memories of her mother’s own birth story came flooding back

“When [my mom] gave birth to me, she was completely alone. Hours went by and nobody went to check on her, “she recalls. “She’s an immigrant, she doesn’t speak English. And if someone did come in and she asked questions, they would make her feel ignorant.”

She had an epiphany: “If this happened to me, and it happened to my mom 34 years ago, what makes me think that anything’s going to change by the time my daughter has a child?”

Cuara began researching our maternal healthcare system and quickly learned that there was a considerable cause for concern. “There are hundreds of thousands of women experiencing this trauma and dying,” she discovered.

“I started asking friends about their birth experience. And most of my friends and my family members were really young and healthy when they had their children. They were giving birth in their early 20s and most of them were by C-section. And it’s like, ‘Wait—why?’”

A system disproportionately affecting Black and Latina women

Cuara identified yet another racial disparity in our maternal healthcare system. Despite having low-risk pregnancies, Black and Latina women are significantly more likely to deliver by C-section.

“Doctors make C-sections sound like normal procedures, but they’re not, they’re serious surgeries. Deeply invasive,” Cuara stated.

“And you’re sent home to care for a newborn with an incision that you’re healing from. Typically, after a big surgery, you’re told, ‘Get some bed rest. Stay off your feet. Eat this. Come back and follow up,'” she says. “When we have c-sections, we’re sent home and told to take care of someone else.”

An even more disheartening discovery: socioeconomic status and access to healthcare are not primary factors. This was proven in the tragic death of Shalon Irving. The successful and educated epidemiologist succumbed to fatal postpartum complications following her C-section. She was Black.

Cuara spoke on this phenomenon, adding, “It’s not about insurance, it’s not about finances, it’s not about class or anything like that. It’s really about the color of your skin.”

A study on maternal morbidity supports this unconscious bias theory, concluding that black, college-educated women were still more likely to experience severe complications during pregnancy and childbirth than white women who didn’t graduate from high school.

Cuara eventually nursed herself back to health

“A lot of the pain was coming from my back, which is where the epidural had been injected,” she shared.

“So, I started using this method called belly binding. It’s been used for years but we don’t really use it in the U.S. That’s where the products [for Misty Phases] originated.”

Combining all she had learned along with her own experiences, Cuara decided to launch Misty Phases. “The U.S., despite being a developed country, is actually the worst place to give birth,” she disclosed. “And the numbers of maternal deaths are increasing — it’s not getting better.”

Her brand’s mission is to advocate for better maternal care for mothers. “We really need your help —doctors, family members, friends. We just gave birth. [Women] need help to recover. That’s number one,” she said.

“Number two is to raise awareness about the inequalities in our maternal healthcare system. We need to share what’s going on, how mothers are dying, how mothers are becoming sick. I think that will cause change.”

Her brand is helping other women heal

Cuara swears by the healing and compressive powers of the belly binders and girdles sold at Misty Phases. These products soothe myriad ailments, like back pain and muscle separation. But if you purchase one, you’re not just helping yourself — you’re also helping displaced or unhoused mothers.

“For every item that’s purchased, we donate a postpartum recovery underwear,” Cuara added.

“It’s an underwear that keeps you compressed, which helps with both vaginal or C-section births.”

They work directly with pregnant and postpartum women living in shelters and camps to deliver these valuable donations.

Cuara’s advice to expecting mothers? Don’t be afraid to ask for help.

“If you’re not okay, the baby’s not going to be okay. Put yourself first and don’t be afraid to ask for help. We’re so ashamed to ask for help, we’re so ashamed to say we can’t do it, or ‘I’m tired today’ or ‘I’m in pain’ or ‘I don’t know what I’m doing.’ It’s okay to ask