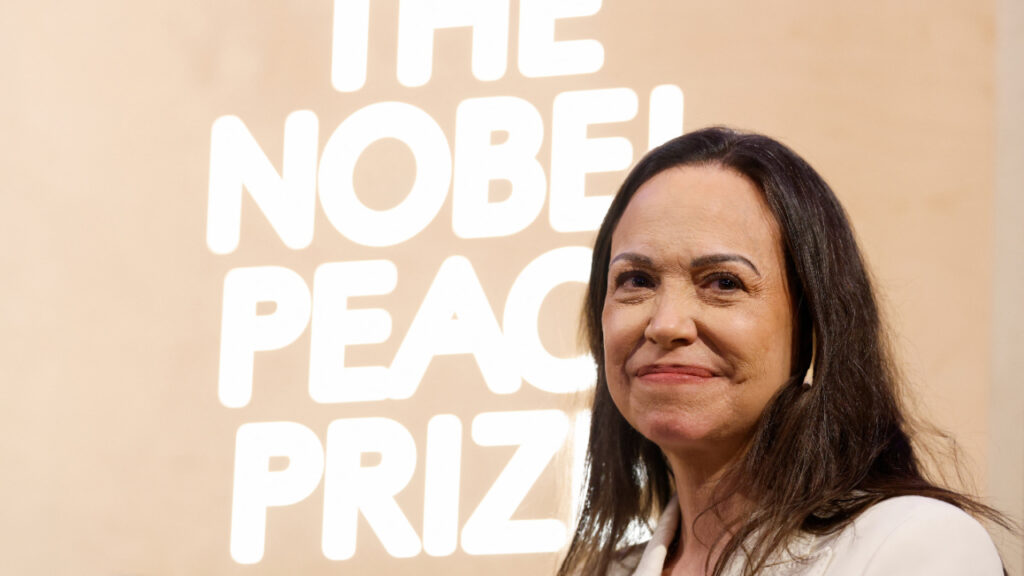

María Corina Machado Crossed Checkpoints, Rough Seas, And A U.S. Airstrike Corridor To Reach Oslo

The woman the Nobel committee calls “a brave and committed champion of peace” did not arrive in Oslo on a red carpet. She arrived soaked, exhausted, and fresh off a wooden fishing boat that sailed through a corridor where U.S. airstrikes have destroyed similar vessels and killed dozens of people in recent months.

María Corina Machado spent more than a year in hiding in Venezuela. She faced an arrest warrant, a travel ban, and public threats from the Maduro government. She still chose to risk a 10-hour escape by land and a long, dangerous night at sea to collect the Nobel Peace Prize and tell the world, in her own words, that Venezuela has become “the criminal hub of the Americas,” as she said during a press conference in Oslo, according to The Washington Post.

Her journey looked like a political thriller. It also mirrored the clandestine routes that millions of Venezuelans use to flee the same country she vows to democratize.

A 10-hour escape that reads like a movie

According to The Wall Street Journal, Machado left a safe house in a Caracas suburb on Monday afternoon wearing a wig and a disguise. She had lived in hiding for about a year. Venezuelan authorities had barred her from leaving the country and warned that she would become a “fugitive” if she tried to travel to Norway.

From that undisclosed hideout, Machado started a 10-hour drive toward the coast. A person close to the operation told The Wall Street Journal that she and two people helping her escape crossed 10 military checkpoints on the way to a fishing village, each one a possible point of arrest.

The plan had been in the works for about two months. A Venezuelan network that has helped others flee coordinated the route and timing. “We coordinated that she was going to leave by a specific area so that they would not blow up the boat,” that source said, referring to U.S. military operations against vessels suspected of drug smuggling in the same waters.

Machado reached the coast by midnight and rested for only a few hours. At dawn, the next phase began.

How María Corina Machado slipped through 10 checkpoints and a sea corridor

At 5 a.m., Machado boarded what The Wall Street Journal describes as a “typical wooden fishing skiff” and left the Venezuelan shore for Curaçao. Strong winds and choppy seas slowed the small boat, according to the same report.

Her team made a “crucial call” to the Trump White House before the boat left, asking U.S. officials to avoid striking the vessel in a zone where U.S. airstrikes had already hit more than 20 boats in three months and killed around 80 people. “We coordinated that she was going to leave by a specific area so that they would not blow up the boat,” the person close to the operation told The Wall Street Journal.

Around the same time, two U.S. Navy F-18S entered the Gulf of Venezuela and circled near the route that leads from the coast to Curaçao for roughly 40 minutes. It was the closest incursion of U.S. aircraft into Venezuelan airspace since the U.S. buildup in the Caribbean began.

Machado later confirmed in Oslo that “yes, we did get support from the United States’ government,” when asked about the operation, NBC News reported. “I cannot give details, because these are people who could be harmed,” she added.

The Caribbean crossing, U.S. fighter jets, and a very wet boat ride

If the route sounds abstract, the conditions onboard were not. CBS News interviewed Bryan Stern, a U.S. special forces veteran and head of the Grey Bull Rescue Foundation, who led the maritime part of the extraction.

“It took an American private rescue team 15 to 16 hours to get Venezuelan opposition leader María Corina Machado out of her country and safely on her way to Norway,” CBS News reported. Stern told the outlet that the vast majority of that time happened at sea, in rough conditions. “No one’s blood pressure was low, throughout any phase of this operation, including mine,” he said. “It was dangerous. It was scary. The sea conditions were ideal for us, but certainly not water that you would want to be on.”

Stern described a nighttime rendezvous somewhere in the Caribbean. “The maritime domain is the most unforgiving. This was in the middle of the night, very little moon, a little bit of cloud cover, very hard to see, boats have no lights,” he said. By the time Machado boarded his boat, “all of us were pretty wet. My team and I were soaked to the gills. She was pretty cold and wet, too. She had a very arduous journey.”

He added a detail that strips away the grandiosity and keeps the human: “No one was enjoying that ride, especially Maria!”

After hours at sea, Machado reached a safe location and then Curaçao. From there, she boarded a private jet that stopped in Bangor, Maine, before flying on to Oslo, The Wall Street Journal reported.

Why María Corina Machado says Venezuela is already “invaded”

The moment she reached Norway, Machado shifted from clandestine escapee to global political actor. She missed the formal Nobel ceremony. Her daughter, Ana Corina Sosa, accepted the Peace Prize and delivered her speech. Hours later, Machado appeared on the balcony of Oslo’s Grand Hotel, waved to supporters, and sang the Venezuelan national anthem with them.

In a press conference in Oslo, she framed Venezuela’s crisis in terms that echo U.S. security language. “Some people talk about invasion in Venezuela, the threat of an invasion in Venezuela, and I answer, ‘Venezuela has already been invaded,’” she said, according to The Washington Post.

“We have the Russian agents, we have the Iranian agents, we have terrorist groups such as Hezbollah, Hamas, operating freely in accordance with the regime. We have the Colombian guerrilla, the drug cartels that have taken over 60 percent of our population, and not only involving drug trafficking but in human trafficking, prostitution,” she said, calling the country “the criminal hub of the Americas,” The Washington Post reported.

She argues that the Maduro government finances itself with “gold smuggling, human trafficking, drugs and illegal oil sales,” and has repeated calls for the international community “to cut those inflows” of criminal resources, according to The Washington Post and NBC News.

At the same time, some of those claims remain disputed. The New York Times notes that there is no conclusive evidence that Hezbollah and Hamas operate in Venezuela, and that Venezuela’s largest corporate partner is actually Chevron, the U.S. energy company.

From hiding to the Nobel stage, María Corina Machado leans into global power

The Nobel committee honoured María Corina Machado “for her struggle to achieve a just and peaceful transition from dictatorship to democracy,” as the prize announcement stated, and described her as “a woman who keeps the flame of democracy burning amid a growing darkness.”

Machado has embraced that framing while also aligning herself with Trump’s hard line. In October, when her prize was announced, she dedicated it “to the people of Venezuela and to President Trump for his decisive support for our cause,” NBC News reported.

In Oslo, she repeated that Trump’s actions had made the regime “weaker than ever.” She praised the U.S. decision to seize a Venezuelan oil tanker off the coast as part of a wider strategy to cut Maduro’s funding.

Critics see a different story. Protesters in Oslo held signs that read “No Peace Prize for Warmongers,” NBC News reported. Government officials in Caracas have called her a “terrorist” and accused her of asking for a foreign invasion. Jorge Rodríguez, president of Venezuela’s parliament, argued that giving the Nobel to someone “who calls for military action against Venezuela and celebrates the killing of human beings in the Caribbean” showed “the hypocrisy of peace organizations.”

Machado did not give a direct yes or no when asked if she supports U.S. military intervention. “We didn’t want a war, we didn’t look for it… It was Maduro who declared war on the Venezuelan people,” she told the BBC. She insists that what she wants is international help to cut criminal financing and support a “peaceful transition.”

Her own allies sometimes worry about her safety and strategy. Stern told CBS News that he advised her “point blank” not to go back to Venezuela. “I think she’s crazy,” he said. “They call her the Iron Lady for a reason. I told her, ‘Don’t go back.’”

She has already decided otherwise. “Of course I’m going back,” she told the BBC. “I know exactly the risks I’m taking.”

What María Corina Machado’s escape means for the fight back home

Machado’s journey to Oslo ends one chapter. It opens a complicated new one for the Venezuelan opposition.

On one side, exile can drain power. Venezuela has a long list of opposition figures whose influence faded once they left, including Juan Guaidó and Leopoldo López. Critics in state media have called the Nobel ceremony her “political funeral,” as The Guardian reported.

On the other side, her supporters argue that this escape could amplify her voice at a decisive moment. The Associated Press notes that she unified the opposition in 2023, won the primary with more than 90 percent of the vote, and then saw her stand-in candidate, Edmundo González, win the 2024 presidential election by a landslide, according to opposition tallies and independent audits, before the government declared Maduro the victor.

Now, from Oslo, she promises to tour European capitals and eventually visit Washington to build more pressure on Maduro. She has framed her return as a question of timing, not intention. “I came to receive the prize on behalf of the Venezuelan people, and I will take it back to Venezuela at the correct moment,” she told reporters. “Of course, I will not say when that is.”