Revealed: The Government’s Quiet Program to Collect Migrant Children’s DNA

When Customs and Border Protection swabbed a 4-year-old migrant child’s cheek. Then, they sent her DNA to the FBI, and it wasn’t an isolated case. It was part of a sweeping genetic surveillance program that’s quietly built one of the largest DNA archives of migrants in the country—children included.

According to records reviewed by WIRED, U.S. immigration authorities have collected the DNA of more than 133,000 migrant children and teens since 2020. Federal enforcement now stores those samples in CODIS, a federal law enforcement database designed to track violent offenders and sex criminals.

But most of the people whose DNA was collected were not accused of any crime.

Why is the government treating migrant children like future suspects?

The program accelerated after a 2020 rule change from the Department of Justice. The ruling allowed the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to collect DNA from virtually all detained migrants. Even in civil, not criminal, custody. DHS and CBP policies say individuals under 14 are generally exempt, but field officers can use their discretion. And they have.

The records, published earlier this year on CBP’s website and analyzed by WIRED, include at least 227 children aged 13 or younger, and more than 30,000 teenagers between 14 and 17. One case, dated May 10, 2024, involved a 4-year-old Cuban child detained in El Paso, Texas. CBP swabbed her mouth and submitted her DNA to the FBI for processing.

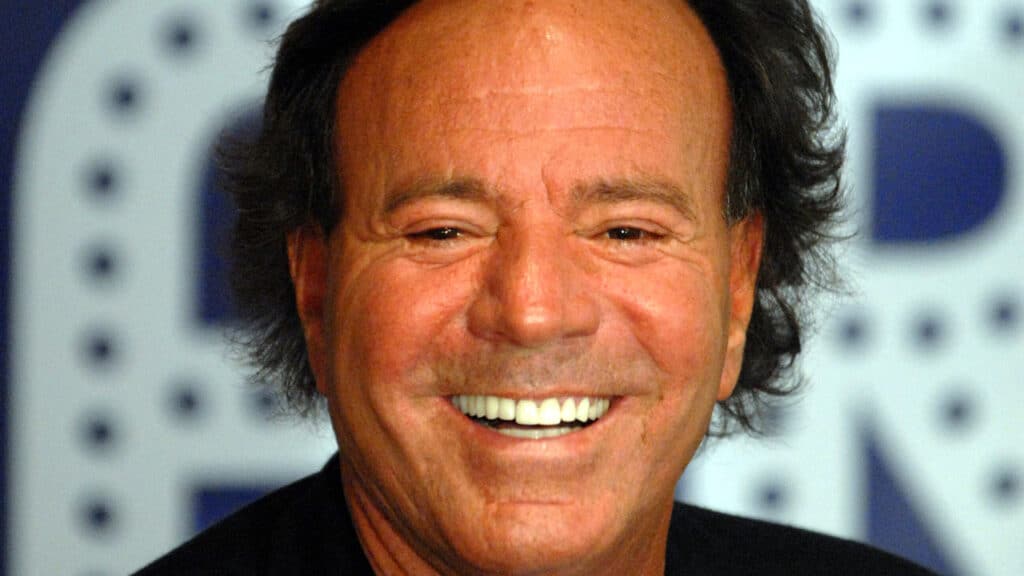

“In order to secure our borders, CBP is devoting every resource available to identify who is entering our country,” said Hilton Beckham, assistant commissioner of public affairs at CBP, in a statement to WIRED. “We are not letting human smugglers, child sex traffickers, and other criminals enter American communities.”

However, legal experts and civil liberties advocates argue that there’s a significant disconnect between public safety and the actual situation.

“It’s horribly dystopian,” said Vera Eidelman, senior staff attorney at the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project. “It’s impossible for me to think of a reason to collect a 4-year-old’s DNA and upload it to a database that’s explicitly supposed to be about criminal activity.”

The DNA of migrant children is now part of CODIS—what does that mean?

CODIS, short for the Combined DNA Index System, is run by the FBI and used across local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies. It matches DNA from crime scenes with stored profiles of individuals, typically those arrested or convicted of serious crimes.

But now, according to the Center on Privacy and Technology at Georgetown Law, DNA from migrants—most of whom have no criminal record—is becoming a growing portion of that database. A 2024 report from the Center found that DHS has added over 1.5 million DNA profiles since 2020, a 5,000% increase in just three years.

If that pace continues, one-third of all DNA profiles in CODIS by 2034 will have been collected by DHS, the report warns.

“Taking DNA from a 4-year-old and adding it into CODIS flies in the face of any immigration purpose,” said Stevie Glaberson, director of research and advocacy at the Center. “That’s not immigration enforcement. That’s genetic surveillance.”

Are migrant children being criminalized before they grow up?

Critics argue that the DOJ’s rationale—that collecting DNA now could help solve future crimes—is deeply flawed.

“It’s not a fair system to keep DNA of people who have not committed crimes on the assumption that they likely will,” said Sara Huston, a genomics policy expert at Northwestern University. She told WIRED that DNA should only be collected with due process, not as a preventive surveillance tool.

And despite DHS claims that DNA is only taken when “required,” CBP’s own data contradicts that. Of the 227 children under 14 whose DNA was collected between 2020 and 2024, only five were listed as having any criminal charges, WIRED reported. The rest were simply labeled “detainee.”

Glaberson points out that under criminal law, there are at least some limits to how and when DNA can be taken. But under immigration law, being “detained” is enough—even though that term can include everyone from asylum-seekers to children in temporary shelters.

What happens to the DNA once it’s collected?

CBP uses buccal swab kits, which are cotton swabs that scrape the inside of a person’s cheek, to collect DNA. The sample, which contains their entire genetic code, is sent to the FBI, where it’s processed into a DNA profile and stored in CODIS.

The FBI says the profiles are used only for identification, not to analyze health conditions or traits. However, experts warn that the raw DNA sample may be stored indefinitely, raising concerns about what future administrations or technologies might do with it.

According to The Guardian, CBP insists it doesn’t store the DNA itself. But once it’s in the FBI’s hands, there is no clear expiration date.

“How would it change your behavior to know the government had your saliva, containing your entire genetic code, stored indefinitely?” the Georgetown report asked. “Would you feel free to attend protests? To seek medical care? To raise your voice?”

The growing surveillance of migrant children is reshaping the border

Since launching its pilot program in 2020, CBP has radically expanded DNA collection. According to WIRED, on just one day in January 2024, the Laredo field office submitted 3,930 DNA samples to the FBI—252 of them were minors.

Advocates say this creates a chilling precedent.

“The program reinforces harmful narratives about immigrants and intensifies existing policing practices that target immigrant communities and communities of color,” said Emerald Tse, a researcher at Georgetown and coauthor of the report. “It makes us all less safe.”

And consent? Experts like Glaberson say many migrants are either unaware of what’s happening or too afraid to say no.

“People who are having their DNA sampled are experiencing it in one of two ways,” she told NewsNation. “They’re either not aware of what’s happening, or they are too afraid to challenge it.”

What migrant children lose when the state collects their DNA

The core of the issue isn’t just about science or surveillance—it’s about what it means to treat a child like a criminal suspect before they’ve had a chance to grow up.

In the name of border security, the U.S. government is collecting genetic material from children as young as four, labeling them as “detainees,” and uploading their identities into a national criminal system—without clear due process, time limits, or consent.

As Huston put it: “CODIS is a wonderful tool. But it was never meant for this.”

And the consequences could last a lifetime.