The Human Cost of the Total Abortion Ban in the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic is one of the few places in the world where abortion is banned under every circumstance. No exceptions for rape. No exceptions for incest. Not even when a woman’s life is at risk. That reality has left women and girls vulnerable to tragedies that activists say could have been prevented.

When the law takes precedence over saving lives

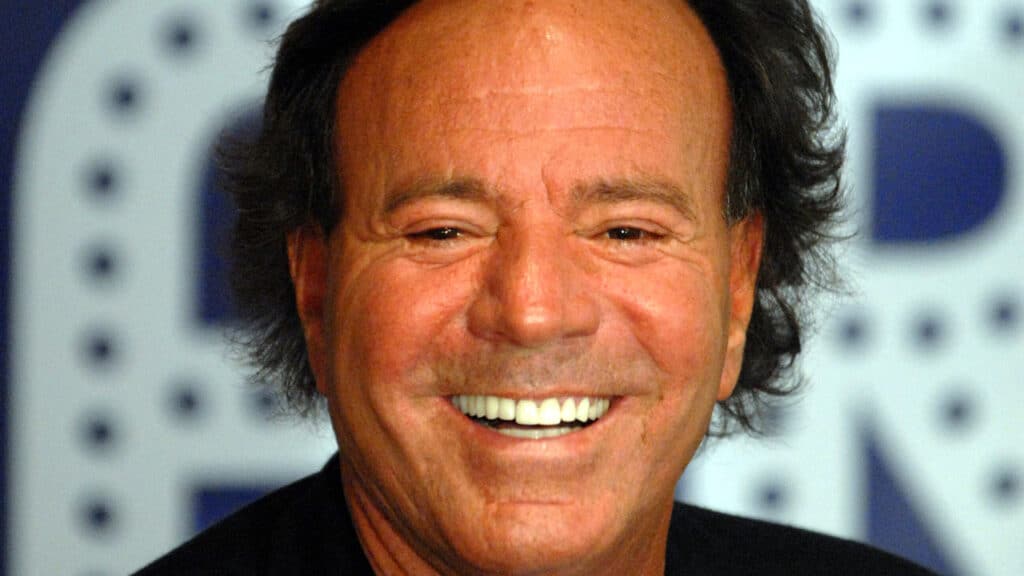

In 2021, 25-year-old Winifer Núñez Beato died during a high-risk pregnancy after doctors refused to intervene. Her case, which left behind a husband and young daughter, became symbolic of the dangers posed by the total abortion ban in the Dominican Republic. Comedian Carlos Sánchez marked the anniversary of her death by posting a birthday cake on Instagram. “It’s a barbarity that in this day and age a mother has to put her life at risk over a risky pregnancy that could be ended. But the law prohibits doctors from doing so,” Sánchez told NBC News.

Other artists have used their platforms to echo this message. Actress and singer Techy Fatule shared the story of Damaris Mejia. She went to three different hospitals with a high fever before dying at home. Fatule explained that doctors could not help her because of the law. She ended her post with the words: “Life is full of exceptions.”

Activists are pushing for the “tres causales”

Women’s rights groups say the law denies them basic protections. Natalia Mármol of the Coalition for Women’s Lives and Rights told NBC News, “This is a fight to guarantee minimum protection for life, health, and dignity for girls and women.” Mármol explained that, without exception, a 13-year-old girl could be forced to carry a pregnancy from rape. Or a woman could die because her pregnancy was not viable.

Groups like Alianza Cristiana Dominicana are campaigning to add exceptions known as the tres causales: when a woman’s life is at risk, in cases of rape or incest, and when fetal malformations are incompatible with life. These exceptions exist across Latin America, where countries like Colombia and Argentina have moved away from total bans.

Maternal deaths under the total abortion ban in the Dominican Republic

The public health toll is already visible. According to NBC News, there have been 100 documented maternal deaths in the country this year. Many of these cases, women’s rights advocates argue, could have been prevented if doctors were allowed to provide abortion care.

Data reinforces those fears. Human Rights Watch has reported that unsafe abortion is now one of the leading causes of maternal death in the country. A 2025 study in Social Science & Medicine found that the constitutional ban on abortion in 2009 was associated with an increase in neonatal mortality and a decrease in contraceptive use. Researchers estimated an additional 6.3 neonatal deaths per 1,000 live births and a nearly 10 percentage-point drop in modern contraceptive use after the law was enacted.

Faith, politics, and a divided society

The Dominican Republic is deeply conservative, with Catholicism as its official state religion, dating back to a 1954 concordat with the Vatican. Both the Catholic Church and evangelical groups support the ban. President Luis Abinader previously voiced support for exceptions but backed the new penal code in August 2025 without them. After signing it, he admitted, “It’s not ideal, but it’s the best possible, since, among other things, it substitutes legislation that dates back to 1884,” according to NBC News.

Still, feminist groups continue to push for reform. In 2021, they camped outside the National Palace for two months, demanding change. Artists and activists today keep their stories alive on social media, insisting the law can still be modified before it takes effect in 2026.

The future of reproductive rights in the Dominican Republic

The fight over abortion has become a fight over what kind of society the Dominican Republic wants to build. Caribbean-pop artist Issade called the penal code “crazy,” “dictatorial,” and “feudal.” She asked, “What kind of society are we constructing?”

For women like Núñez Beato and Mejia, the law had already decided their fate. For advocates, the question is whether the country will continue to prioritize politics and religion over the lives of women and girls.